As published at Philanthropy.com, by Andy Semons and Will Hajjar

It’s a slow but steady evolution: More and more marketers are migrating from companies to nonprofits. But most charities are still far from marketing-centric, and few have board members with expertise in the field. That can make it hard to get buy-in for a bigger marketing budget, and it may require you to defend or justify the cost of your work.

However, if you use data to back up your claims, and speak in terms your trustees understand, you’ll stand a much better chance of getting approval for a bigger investment in marketing and communications.

To help you make a strong case, here are several techniques marketers at nonprofits have employed successfully to win support for budget increases. You can adapt these approaches to fit your organization’s needs.

1. First, drop the marketing jargon. Terms like “brand positioning,” “core benefits,” and “brand imagery” may be unfamiliar to trustees. However, your board members should understand the notion that a higher profile for the institution can lead to more donations. So build your case on this premise ― and use data to demonstrate how money spent on raising your nonprofit’s profile and acquiring new donors will result in more revenue.

2. Figure out how much you need to spend on advertising to get positive results. A good data analyst can use basic metrics about the public’s awareness of your organization, combined with sector-wide spending on advertising and reported revenue, to determine the “breakthrough” cost; that is, the amount of money you should invest to produce a positive return for your organization. This estimate will enable you to set benchmarks and projections for specific time periods, which you can share with your board in your budget forecasts. This analytical rigor is rare among nonprofits, but it provides a level of clarity your trustees will appreciate.

The analyst will need to make a number of assumptions about your key competitors. These considerations include how likely it is that their spending will increase, decrease, or stay the same, along with external market factors (such as issues in the news, the state of the economy, changes to laws, etc.). The relevant factors may differ according to the particular mission of a nonprofit and the market it serves.

You don’t need to spend a lot of money; even small nonprofits can gather data on their competitors, such as the “ad spend” and the revenue raised. Find a data-analytics firm that will work with you to identify, for the purposes of the study, your key competitors and sources of data about them. The Data and Marketing Association offers a list of analytics companies that can help you.

If your organization doesn’t have current “awareness data,” analysts can interview your senior staff to make an educated guess about the relative position of your nonprofit compared with key competitors and help you set some rough benchmarks. Most analytics and advertising firms can access spending data from the research company Kantar Media. You also can purchase, at low cost, data from GuideStar, which tracks donations by organization.

For example, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society needed to establish a budget for the launch of its campaign “Someday Is Today,” which aimed to increase national awareness of the society by 10 percent and donations by 25 percent.

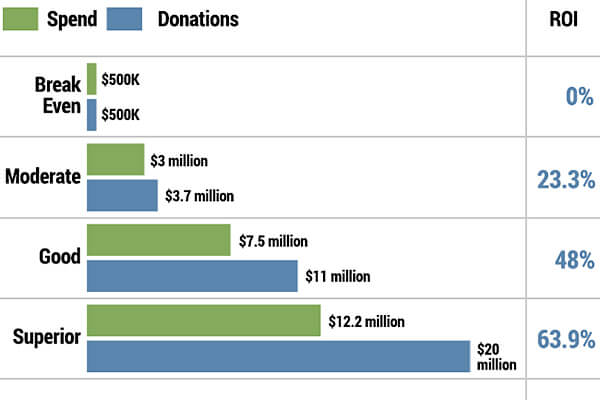

To estimate the right advertising budget, we used data from Kantar to analyze what the organization and its key competitors were spending. Then, based on awareness data the group had already gathered, our analyst used a forecasting formula to calculate the breakthrough cost, or the amount needed to meet the group’s communications goals of greater awareness and more revenue. While the forecasting model can’t be represented by a simple equation, it does take into account three key variables:

• Awareness, which depends on an organization’s advertising budget and other factors, such as media coverage and endorsements.

• Revenue from all types of donors, which is driven in part by awareness.

• Return on Investment, or the amount of revenue you must raise to exceed the marketing expenses.

Knowing the breakthrough cost allowed us to forecast how spending different amounts on marketing would affect giving. Then, with input from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, we developed a budget for the campaign that increased spending on marketing and projected an increase in revenue.

Contributions for that year were nearly double the fundraising goal. The following year the society’s marketing staff got a further increase in its budget, with little resistance from the board.

3. Collect the data you’ll need to build a strong case for your budget. Numbers don’t lie. So it’s important to develop a consistent way to track metrics on brand awareness and perceptions of the brand (known as brand imagery).

Many nonprofits also like to monitor “claimed intent.” This entails comparing the public’s expressed intent to give money to a specific charity with the amount actually donated.

Using both of these metrics increases the accuracy of your forecasts over time and can give you a competitive advantage. Consider this: According to a Stanford Business School survey, 57 percent of charity boards don’t benchmark their groups’ performance against peer organizations. Those that do have a much better idea of what they’ll need to spend in the coming year to boost their revenue.

Before the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society launched its “Someday Is Today” campaign, we helped the group measure a number of factors, including brand awareness in comparison with that of key competitors; intent to donate in the future; and perceptions of the organization as a leader in science and discovery, which is a main theme in the organization’s communications strategy.

We pulled these data points, as well as overall donations, into a performance dashboard, an easy-to-follow spreadsheet that tracked key metrics and was updated twice a year at both the national and regional levels. This information helped the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society understand how to optimize its messages and allocate spending in pivotal markets.

4. Put your own data in the context of your competitors. Tracking data regularly can do much more than provide an ongoing barometer of campaign performance. It can help you make the connection between the amount spent on advertising and the competitive advantage you’ll gain or lose if you alter your spending. That’s the “holy grail” of budget planning.

Take another nonprofit, the City of Hope Medical Center in Los Angeles. After running its “Miracle of Science with Soul” awareness-campaign for several years, the nonprofit reached the highest level of brand recognition among its competitors. Yet, as too often happens, when the center increased its advertising budget, so did its key peers, which led to a decline in awareness of the City of Hope.

The organization wanted to understand, based on its competitors’ behavior, how much it needed to spend the next year to maintain the level of awareness, or better yet, boost it. To do so, we combined the group’s data from three consecutive years with Kantar’s data about spending on advertising by the center’s peers. In particular, we looked at yearly changes in “share of voice”: the amount City of Hope spent on advertising compared with the total spent on advertising by the center and its designated competitors. That provided a longer-term view of the relationship between spending and awareness.

Based on past spending patterns for each competitor, and assessing the market environment, we predicted how much each competitor was likely to spend in the future. Using this data and City of Hope’s expected budget for the next year, we forecast what would happen if the medical center reduced spending by 10 percent, maintained its present budget, or spent 10 percent more.

Because the center’s peers were increasing their investment, we advised City of Hope to do the same to maintain its current level of awareness. We also learned that a boost of 10 percent could yield a 1 to 2 percent increase in awareness. This data gave the center’s executive the information needed to argue for a bigger budget.

Going before your board to ask for more marketing dollars doesn’t have to be an untenable situation. Whether you gather basic metrics or conduct a more rigorous study that ties awareness to greater giving, a little data analysis, combined with a bit of preparation, goes a long way.

Andy Semons is founding and strategic-planning partner at the advertising agency IPNY. Will Hajjar is the global executive director of the management consulting firm Rivelare.